On March 28, 2024, the Japan IP High Court decided to dismiss the appeal filed by Audemars Piguet Holding SA, a Swiss luxury watchmaker, against the JPO’s decision (Appeal No. 2021-013234) to reject TM Application No. 2020-20319 for the device mark representing AP’s iconic “ROYAL OAK” watch collection for lack of both inherent and acquired distinctiveness.

[Court case no. Reiwa5(Gyo-ke)10119]

Audemars Piguet “ROYAL OAK” Watch Collection

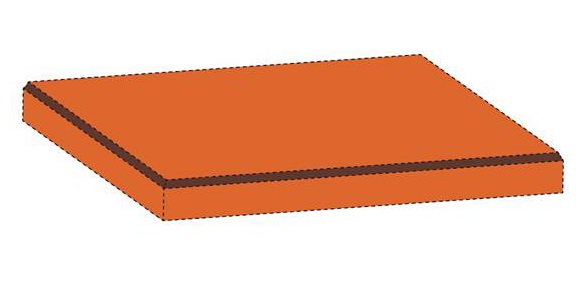

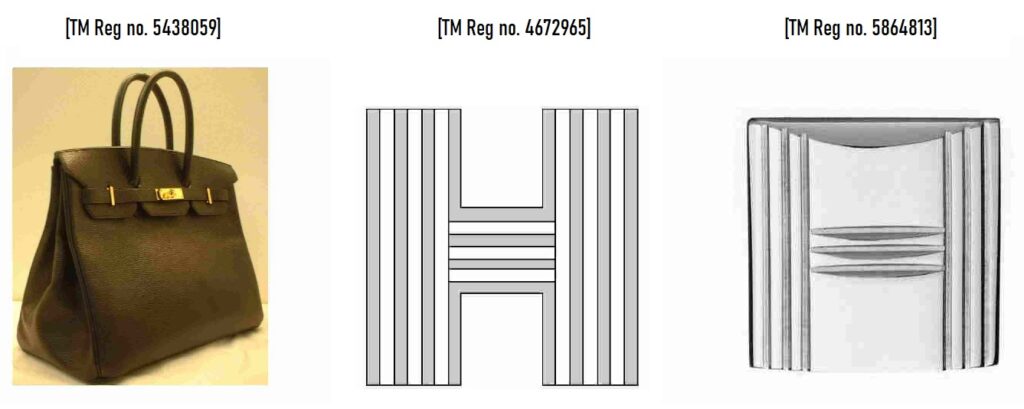

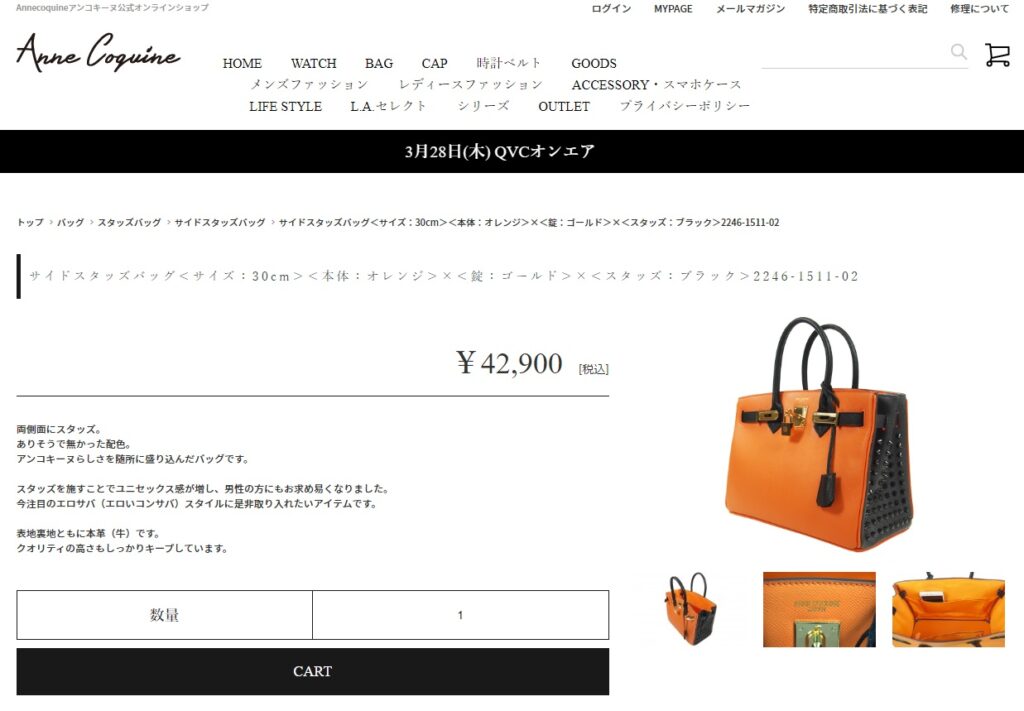

On February 26, 2020, Audemars Piguet Holding SA (AP) filed a trademark application for the shape of the flagship watch collection “ROYAL OAK” (see below) to be used on ‘watches’ in class 14 with the Japan Patent Office (JPO) [TM application no. 2020-20319].

The mark consists of a dial with tapisserie pattern and hour markers, minute track, date window, an octagonal bezel with 8 hexagonal screws, case, a crown, and a lug of the famed “ROYAL OAK” watch collections.

JPO Refusal

On June 8, 2023, the JPO Appeal Board affirmed the examiner’s rejection and decided to refuse registration of the applied mark due to a lack of inherent distinctiveness based on Articles 3(1)(iii) of the Japan Trademark Law by stating that relevant consumers would simply recognize it as a generic shape of a wristwatch, not a specific source indication since many watchmakers have supplied with similar shape to the dial, bezel, case, crown, and lug of the applied mark (see below examples).

Besides, the Board found the produced evidence is insufficient to determine whether the shape per se has acquired nationwide recognition as a source indicator of AP’s watches.

Audemars Piguet Holding SA filed a lawsuit with the Japan IP High Court on October 20, 2023, and disputed inherent and acquired distinctiveness of the applied mark.

IP High Court ruling

- Inherent distinctiveness: Article 3(1)(iii)

In the decision, the judge said “There is no particular circumstance in which the shape represented by the applied mark is taken novel in comparison with the shapes of other wristwatches. If so, it is considered within the range of shapes normally required to achieve basic function of the goods. Even supposing that the shape is unique as a whole, the shape of each component is made in a form suitable for use as a wristwatch, and selected from the viewpoint to achieve the function of the goods. Therefore, the applied mark lacks distinctiveness since it remains within the scope of expected selection of the shape for functional reasons of a wristwatch.”

AP claimed the JPO finding is inadequate because none of competitors watches have the same combination of three unique features, namely, (i) an octagonal bezel, (ii) 8 hexagonal screws, and (iii) tapisserie pattern on the surface of a dial. Visual similarity in one or two components are insufficient to deny inherent distinctiveness of the applied mark.

However, the court did not agree with this allegation and said “It is sufficient to assess whether each shape of components is distinctive as part of the shape of wristwatch”.

- Acquired distinctiveness: Article 3(2)

AP argued acquired distinctiveness of the applied mark as a result of substantial use since 1972. Allegedly, annual sales of the “ROYAL OAK” luxury watches exceed JPY 8 billion on average in the past six years. Each year, AP spent more than JPY400 million on advertisement and promotion in Japan.

In this respect, the court pointed out the “ROYAL OAK” watches have some collections that do not represent three unique features, such as, “Royal Oak Offshore” and “Royal Oak Concept” (see below). If so, the annual sales and expenditures on advertisement and promotion would not all attribute to watches representing the applied mark.

Besides, AP has not produced the result of market research to demonstrate a certain degree of recognition of the applied mark. Accordingly, the court has no reason to believe the applied mark per se has played a role in identifying the source of famous luxury watch, Audemas Piguet.

Based on the foregoing, the court determined that the JPO did not err in its findings and that the application of Article 3(1)(iii) and 3(2) was appropriate. As a result, the court decided to dismiss the appeal in its entirely.